Using mental models to understand complex services

Complex services that involve multiple organisations, tasks and guidelines can be thorny things to research, let alone articulate back to stakeholders. When we were asked to research people’s experience of dealing with difficulties abroad, we immediately knew it had all the hallmarks of a complex service.

To try and make sense of such knotty problem spaces, we decided to adapt Indi Young’s mental model approach. A mental model depicts how users behave and what type of support they receive from an organisation at each point along their journey. Using this technique allows us to spot gaps in the services provided by an organisation, and opportunities for improvement.

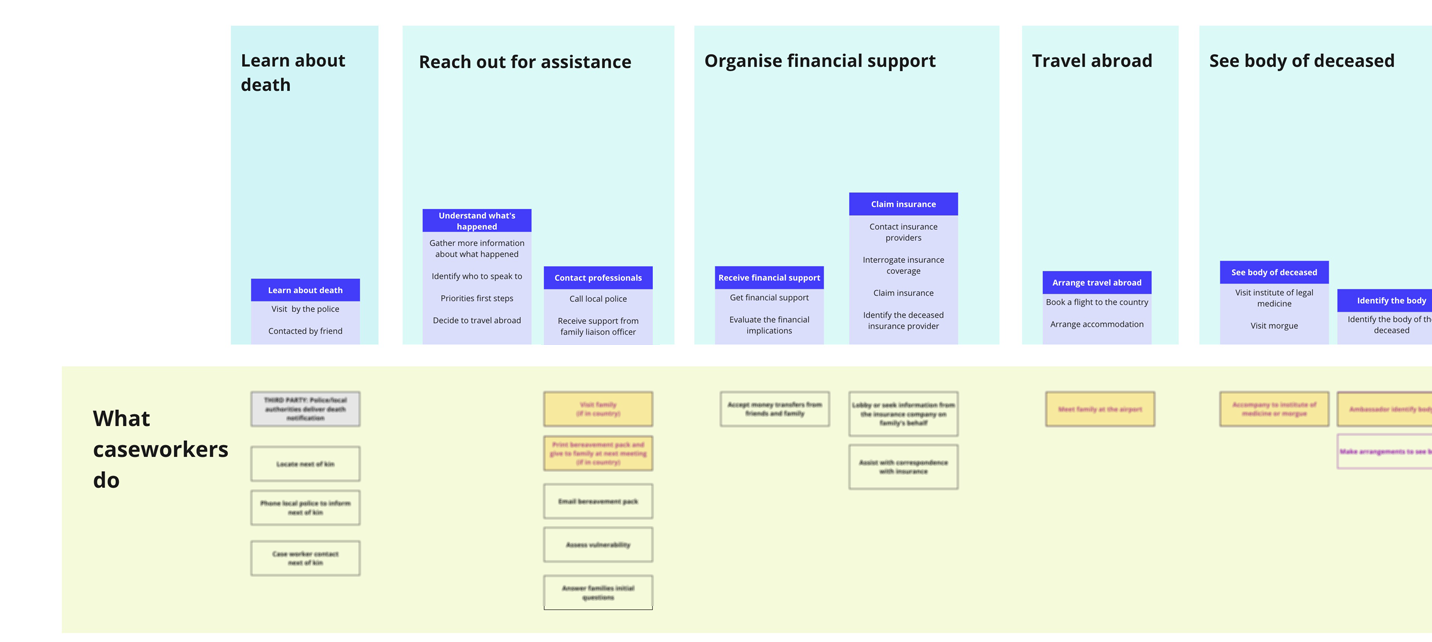

Our mental model had three layers: the top layer depicted users' tasks and behaviours while dealing with a death; the second layer articulated the policy and service that caseworkers provided to support those tasks; the final layer showed all of the GOV.UK content that was available to users. The model gave a holistic view of the way the organisation was supporting users to achieve their goal.

Arranging tasks into task towers

By showing users' tasks and arranging them into task towers (sub-sections of things the user had to do) we could illustrate the entire world that a user has to navigate in order to achieve their goal. We didn’t worry about being strict about the chronology of the towers and mental spaces, as unlike journey maps, when a user did a thing was less important. We also made sure to keep the top layer service agnostic, so that it only represented the user’s tasks and not the current solution.

How policy supports users' tasks

We spent a lot of time interviewing policy makers and reading policy documents so that we could get a good understanding of how the service works from the organisation's perspective. We then aligned the policy underneath the task towers - this helped us see where policy decisions were supporting what users were trying to do and where there were potential gaps in the service offering.

Understanding how caseworkers embody policy

Crucial to the success of the mental model was interviewing caseworkers, so that we could learn how they realised policy. We highlighted within the model where there were variations between what caseworkers did. This helped show where the service maybe wasn’t working as well as it should, and that some users were at risk of not getting a service that others may have.

Findings from casework research brought the policy to life. It allowed us to see the tools that caseworkers use, and the good, the bad and the ugly of the service from their point of view. It allowed us to spot opportunities where something could be done differently - for instance, where a paper form could be replaced with a digital transaction, or where caseworkers were doing something beyond policy (which indicated areas where the service offering could be expanded).

How content supports a service

As a team, we trawled through the content available on GOV.UK to see what information was available to users. This gave us a view of how the service was currently delivered online, and the artefacts that had been created to support the task towers. We found there was guidance and resources available, but were often not where users expected or not entirely what they needed.

We also found lots of similar content, or conflicting guidance, meaning that certain task towers were bloated with information that could confuse or overwhelm users.

Users' tasks remain stable over time but services changes

The beauty of the mental model is in its longevity: users' tasks should remain stable over time, so the top layer of the mental model is something that we can continuously refer back to. What can and should change is the service offered by the organisation. This mental model can serve as a tool every time we’re thinking about how we might improve the service in the future.